By Expressões Aanarquistas – Fenikso Nigra

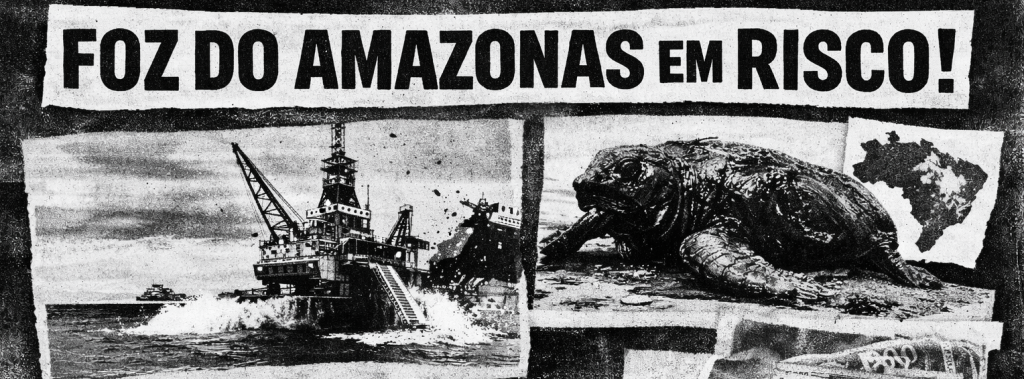

On January 4, 2026, Petrobras reported a leak of 18.44 cubic meters of drilling fluid at the Morpho well, 175 kilometers off the coast of Amapá, at the Amazon River mouth. The incident occurred just two months after the environmental license for oil exploration in the region was granted—a license released under political pressure and contradicting technical opinions from Ibama’s own staff.

The incident is not a deviation from course. It is the confirmation of a pattern. Decisions about territories and natural resources continue to be made by centralized power structures that operate far from affected territories and the communities that depend on them. Local knowledge, traditional ways of life, and documented environmental risks become obstacles to be circumvented when they collide with economic interests.

Since 2014, Petrobras has sought authorization to drill at the Amazon River mouth. In 2023, Ibama denied the first license due to insufficient impact studies and high risks to unique ecosystems. The region harbors the planet’s largest continuous mangrove belt, recently mapped Amazon reefs, and fishing communities whose survival is directly linked to the health of these environments.

The technical denial was quickly converted into a political problem. The federal government began treating environmental resistance as an obstacle to development. The pressure to release the license before COP30 in Belém revealed the contradiction between international climate discourse and domestic practice. While energy transition was defended on global stages, a new fossil exploration frontier was opened in a sensitive area.

This duality is not personal incoherence of rulers. It is a structural characteristic of states embedded in a commodity-dependent economy. Environmental discourse functions as diplomatic capital; resource exploitation, as fiscal and political engine.

The absence of prior consultation with traditional communities violates ILO Convention 169. Many potentially affected populations did not even have adequate access to information about the project. Still, their territories are treated as sacrifice zones in the name of a “national interest” defined without them.

The risks are not abstract. Scientific modeling indicates that a major leak in the region could reach multiple countries along the northern coast of South America and the Caribbean. Ocean currents, depth, and ecological sensitivity make the area particularly vulnerable. Mangroves, reefs, and estuaries—nurseries of marine life—would be directly hit.

The January 2026 leak was classified as small. Small for industry statistics. Not for those who live from the sea. Not for ecosystems that accumulate impacts over time. Each incident reveals that risk is not hypothetical; it is operational.

Developmentalist logic presents oil as national necessity, promise of employment and revenue. But it rarely answers the central questions: who receives the benefits? who assumes the risks? who decides? The concentration of profits contrasts with the socialization of environmental damage.

When surveys show popular rejection of exploration in the region, this reveals a mismatch between institutional decisions and social will. Representative democracy reveals its limits when territories are negotiated as economic assets.

Experiences in Latin America demonstrate that other forms of decision-making are possible. Popular consultations, territorial assemblies, and community management show that local populations can decide their own destinies. Where communities have real veto power, extractivist logic finds limits.

The problem is not just a specific license, but the structure that allows governments and corporations to decide about territories they do not inhabit. States and companies share the same rationality: transforming nature into resource, territory into asset, life into economic variable.

From the communities’ perspective, sovereignty is not national flag or diplomatic rhetoric. Sovereignty is autonomy over lived territory. It is the power to say no. It is collectively deciding the limits of what can or cannot be exploited.

Strengthening the self-organization of indigenous peoples, quilombolas, and traditional communities is more than a resistance strategy; it is the construction of real alternatives to the predatory model. Solidarity networks, information circulation, alliances between countryside and city, and independent technical support expand territorial defense capacity.

The Amazon River mouth case reveals a future project based on continuous expansion of extraction frontiers. But this future is not inevitable. It depends on power correlations, and power correlations can be transformed.

The 2026 leak was small. The next ones may not be. With hundreds of exploratory blocks on offer, the region risks becoming a new oil frontier. The choice is political, not technical.

Between life and profit, between living territories and sacrifice zones, no neutrality is possible.

Defending the land is not abstract ideology. It is a condition of existence.

In struggle we continue—dignified, free, and untamable.